Symbolic light in van Eyck

As we look at the Annunciation, we become warmly conscious of the gentle radiance of the light, illuminating everything it embraces, from the dim upper roofing to the glancing gleam of the angel's jewels. The clarity would be too intense were it not also soft, an integrating, enveloping presence. This diffused presence, impartial in its luminescence, is also a spiritual light, surrogate of God Himself, who loves all that He has made.

The symbolism goes even deeper: the upper church is dark, and the solitary window depicts God the Father. Below though, wholly translucent, are three bright windows that remind us of the Trinity, and of how Christ is the light of the world. This holy light comes in all directions, most obviously streaming down towards the Virgin as the Holy Spirit comes to overshadow her: from this sacred shadow will arise divine brightness. Her robes swell out as if in anticipation, and she answers the angelic salutation ``Ave Gratia Plena'' (``Hail, full of grace'') with a humble ``Ecce Ancilla Domini'' (``Behold the handmaid of the Lord''). But with charming literalness, van Eyck writes her words reversed and inverted, so that the Holy Spirit can read them. The angel is all joy, all smiles, all brightness: the Virgin is pensive, amazed, unbejewelled. She knows, as the angel apparently does not, what will be the cost of her surrender to God. Her heart will be pierced with grief when her Child is crucified, and we notice that she holds up her hands in the symbolic gesture of devotion, but also as if in unconscious anticipation of a piercing.

The angel advances over the tiles of a church, where we can make out David slaying Goliath. (Goliath represents the power--ultimately fruitless--of the Devil.) The message the angel gives Mary sets her forth on her own road to the giant-slaying that is her motherhood and holiness.

Here is a link to further explanation of all the symbols in this painting. (just hit the title of this post and it will bring you there) http://leesandlin.com/reviews/97_0808.htm

Friday, December 14, 2007

Van Eyck picture and commentary

Posted by

Tmart

at

8:46 AM

0

comments

![]()

Links to the poetry of John Donne

One of the most beautiful poets expressing

that human and divine interaction. For your Christmas assignment

it may be someone to check out.

Posted by

Tmart

at

8:40 AM

0

comments

![]()

Wednesday, December 12, 2007

Great examples of Story mapping

Check out these two great examples of story mapping--one by Rosie Croghan and the other by Karon Walsh. Great job!

Posted by

Tmart

at

4:57 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: story mapping

Monday, December 10, 2007

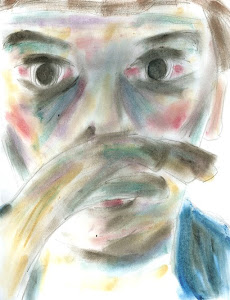

Andre Dubus' "A Father's Story"

A Commentary

"So, He says, you love her more than you love Me.

I love her more than I love truth.

Then you love in weakness, He says.

As You love me, I say, and I go with an apple or carrot out to the barn."

These last lines of Andre Dubus' "A Father's Story" elevate what until the last few pages is a dramatic story illustrating the most perplexing of moral quandries (do we choose love or truth?), into an even more complex theological rumination (Why did God allow his Son to die?; What does it mean that God loves us "in weakness.") Like Thomas Aquinas's theology of grace, this story grasps the reader on two levels--the natural/ordinary (Luke's dilemma between the love of his daughter and the truth to do what is right and just), and the supernatural (Luke's ever-present perception of God becomes the God with whom Luke has an ongoing dialogue by the end). As in Thomas' theology, to grasp the latter of these, one must mine and prod the first (as Luke Ripley has it, "I…have come to believe my life can be seen in miniature in that struggle in the dark of morning'). This essay, thus, begins with the narrative of Luke Ripley, before proceeding to the Christological-narrative revealed in Luke's dialogue with God.

First Narrative: Luke Ripley

Much of the early part of the story, Dubus deftly details both the fractured history and emotional texture of the life of Luke Ripley. He is a divorced father of three sons and one daughter ("It is Jennifer's womanhood that renders me awkward."). His best friend is a Catholic priest with whom he talks of faith and longing ('Belief is believing in God; faith is believing that God believes in you"). We hear of why his marriage fell apart and what his reflection on it and love are now ("I believe ritual would have healed us more quickly then the repetitious talks…perhaps then we could have subordinated feeling to action, for surely that is the essence of love."). We also learn of Luke's perspective on the Church and his faith in it and God ("what I'm really doing is feeling the day, in silence, and that is what Father Paul is doing on his five-to-ten-mile walks.")

The first narrative comes to a head when his daughter Jennifer comes home following an evening out drinking and skinny dipping: "…then the sobs in her throat stopped, and she looked at me and said it, the words coming out with smoke: 'I hit somebody. With the car." Certainly one of the most dramatic moments is when Luke returns to the scene of the accident to see if the accident occurred and if the person his daughter hit is alive. With the full awareness that God is watching his actions, Luke proceeds to feel for life in the dead young man. At one point Luke compares himself to Cain (Where is your brother?) or Job (suffering without reason)--stating that he is not sure which he is closer to (murder/Cain or absurd suffering/Job). Luke then follows up in action what he knew he was going to do the first he heard of what happened: he fails to report the accident, and furthermore, covers up his daughters manslaughter through crashing the car she had used, in front of the church the next morning on the way to Mass. Some scenes between daughter and father in their collusion to cover this crime up--purposely leave the reader uneasy. Can such a secret drive them apart? How is each going to live with this?

Second Narrative: Luke's Love of His Daughter--God's Love of Christ/Mankind

The last few pages beginning with the lines: "I have said I talk with God in the mornings…" elevate this story beyond ethics (was the act he did right or wrong) to: 1) questions of the salvation of Luke's soul, and 2) questions about the nature of the Christian God and salvation understood within its tradition.

The question of whether what Luke did was right obviously has great religious repercussions for Luke. We are left asking: Did Luke's action to cover this up willingly, damage his soul irreparably? The questions of justice for the dead boy and his family and the dignity of that life that was taken by careless and negligent actions by his daughter is one question. The deeper question, however, is the cover-up and how Luke justifies it to himself and to GOD. According to Luke, it is only with God that he battles with this question (not even Father Paul knows). Such an ending is reminiscent of Abraham (Gen 22, and Gen. 18--where Abraham does God's will, even to sacrifice his child in one story, and in the other, challenges the justness of God's order), Job, and even the story of the prodigal son. The question behind it is: What is Luke's duty--to the truth and justice or to the love of his daughter? This is a profound question for us all. One perceptive student to this question said: "We can live without truth but with love, but we cannot live with truth and no love." (Nice job Pat Barrett!).

What if, however, we could do both--both love and do the truth? In this case it would have meant that Luke would have had to turn his daughter in. Luke states that if it was a SON, he could do this as the type of love between son and father mandates that the Father must let the Son be bruised and broken in life. When a father sees this--he is proud of his son. To see and allow this is what a Father's love to a son means. For a father's love for his daughter, however, to let her suffer he seems to infer that if you do not do something to stop the suffering, IT IS NOT LOVING HER. Or in the very least--Luke states--he cannot let this happen because it hurts more to a father to see his daughter suffer, then it does to see his son suffer. In either case, the question here is raised: WHAT IS LOVE? What is the role of allowing another person freedom--and not to intervene--what does this have to do with love?

The last half of a page elevates this story from the questions of Luke's salvation to the questions of the CHRISTIAN UNDERSTANDING OF GOD and the "economy of salvation" (why God became human and suffered and died for humans). This begins with the lines where God actually begins talking to Luke: "And He says: I am a Father too." Luke also speaks to God--both to God as the Father, and to God as the Son. Each line at this point has great theological meaning. The lines of God responding to Luke are the following:

"I am a Father too," "Yes, but I would not lift the cup," "Why? Do you love them less?," "So, you love her more than you love Me," and "Then you love in weakness." This profound exchange between Luke and the Trinitarian God suggests: 1) That God the father also feels for his Son as Luke does for his daughter, 2) That God loves his Son--as a Parent loves their children--allowing them to suffer through the trials of life as they cannot intercede without taking away their freedom, 3) that love manifests itself differently dependent upon the individual, i.e. love in different ways for their needs, and 4) that God--loves us "in weakness." These last lines are meant to hang with us. What does it mean "to love in weakness?"

To answer this, I think it is instructive to examine a few important scripture passages: Abraham (Gen 22), the parable of the two sons (Luke 15), and the crucifixion of Christ (all the Gospels). In comparing how God demands Abraham's obedience to prove his love with the love of the Father in the prodigal son, we can see that Jesus presents a God of unconditional love. The God Jesus reveals in the parable is one of Agape--waiting and happy without judgment for the return of the son. This seems to be the message for us…that God's love is without judgment and always present. Thus, In contrast to the God of Genesis, this could be interpreted as "loving in weakness."

The God Jesus reveals, on the Cross, however, can be looked at several ways: 1) Jesus' love for us--in his total weakness, his love is expressed most, 2) God's love for us--despite our wrong-doing, God loves us so much HE SUFFERS on our behalf so that we can find his love, 3) God-Jesus--the love of the two (Doctrine of the Trinity: God is one being, who exists simultaneously and eternally in three persons) for one another allows the other person to suffer. This very profound ending leaves with Luke responding: "As You love me"--suggesting that God will continue to love Luke despite his action. It also gives us through the analogy of Luke's own love for his daughter, a glimpse into the type of love God the Father might have for his Son, as well as by extension (since he let his own Son suffer on our behalf), for us. Likewise, it also demonstrates Jesus' (the Son's) love for the Father.

What are we to make of this for ourselves? I think there are some great questions to ponder for our own view of love and faith. What does "loving in weakness" mean for us? What does it mean to choose love over truth? What does it mean to view God's love as "loving in weakness" for our own life and faith? Such questions, of course are deeply personal. I find them, however, to be also deeply beneficial in stimulating a deeper awareness of love, responsibility, faith, and my own understanding of God.

Posted by

Tmart

at

10:00 AM

54

comments

![]()